The Kii Peninsular & Japanese Alps

Revising the Noto Peninsula & the Alps Itinerary

Following the tragic Ishikawa Earthquake that struck the Noto Peninsula on New Year’s Day, we have come to the conclusion that our Noto Peninsula & the Alps Itinerary has to change both for this year and likely for years to come. It is a decision we hoped not to have to take, but based on the feedback from our team on the ground and conversations with hoteliers with whom we work in the area, it is clear that the first part of the tour is not viable.

This article in the Japan Times gives a sense of the destruction that the earthquake has waged. Knowing how reliant the Noto Peninsula is on tourism, we had hoped to be part of the recovery by continuing to travel there and spend our money, but the damage has proven to be worse than first feared.

With tours booked to the area in both the spring and the fall, it left us with a conundrum that we believe we have solved by meshing together a tour we planned to launch in 2025 with the second part of the Noto tour where the damage was less significant. This hybrid tour doesn’t permit a big launch, but it does mean that we can still offer a great tour for those already signed up and for anyone still keen to travel to the area.

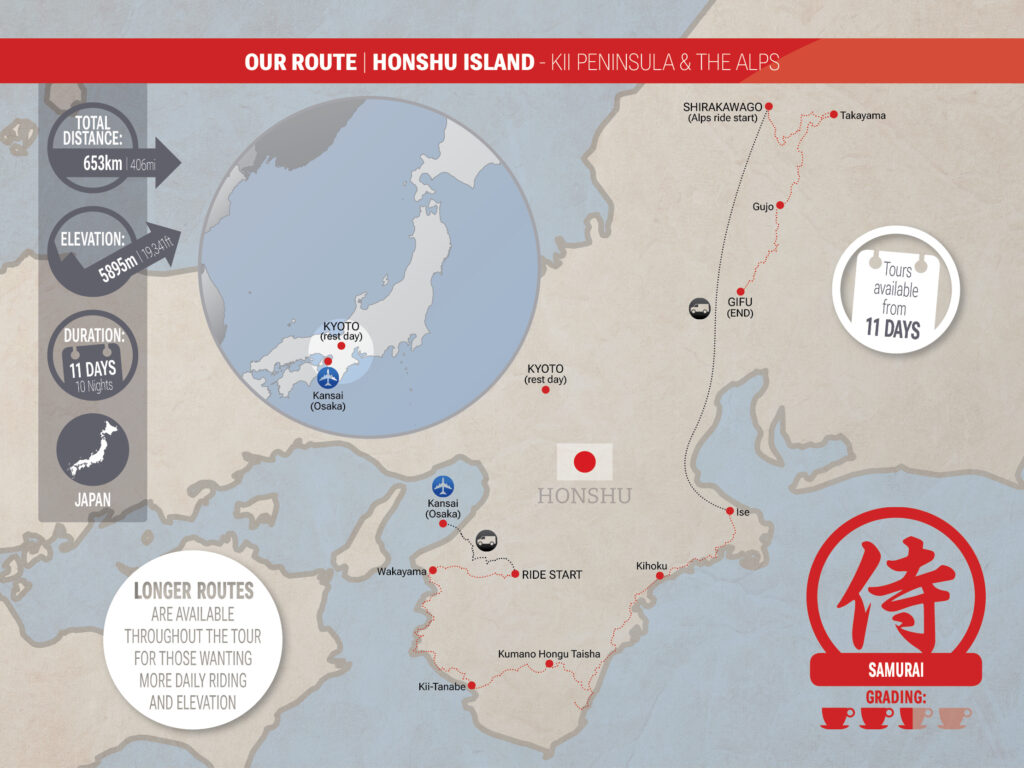

The new tour will visit a different Peninsular that we are very much looking forward to exploring with you – the Kii Peninsula – which is highlighted below with Wakayama, the start point of a ride that intersects with the enchanting Kumano Kodo Pilgrimage that is considered to be the spiritual heartland of Japan.

We describe the Kii Peninsular below, and the new itinerary is also covered. The plan is to ride the first part of the tour around the Kii Peninsula, taking in the most picturesque parts of the coastline and visiting the shrines of the Kumano Kodo. We finish this leg in the sacred destination of Ise, which also happens to be home to our favourite brewery that serves beer and oysters!

The second part gives the riders a chance to experience the Japanese rail system whilst the vehicles transfer the bikes to Shirakawago in the Japanese Alps, where we rejoin the original Noto itinerary and ride to Gifu for a final dinner taking in the ancient art of cormorant fishing. It is a stunning 11-day journey that isn’t just a ride; it’s a passage through time, a communion with nature and an exploration of ancient lands.

We really hoped to maintain the original itinerary, but circumstances make that impossible. The ‘new’ tour that meshes a new tour with parts of the existing itinerary is a solution we are proud of and look forward to riding in the future. Hopefully, we’ll be able to add the Noto Peninsular to it once the repairs have been done. The new tour is graded the same as a 3-cup tour, and the logistics for getting to and from the tour remain the same.

The ‘NEW’ Itinerary

Day 1: Meet and Greet at Kansai Nikko Hotel at Kansai Airport. We build bikes here and leave any bike cases here before heading out for a welcome dinner and presentation of the tour.

Day 2: Cycle to Wakayama City. There is no big transfer as per previous editions of the original itinerary, as the Kii Peninsular is to the south of Osaka, and Wakayama is in the Kansai prefecture. So, for this itinerary, we are straight on the bikes for a gentle ride to the historic city of Wakayama, which also serves as the starting point for many of the pilgrims on the Kumano Pilgrimage.

Day 3: Cycling to Kii-Tanabe and Exploring the Area

Embark on your cycling journey to Kii-Tanabe. Along the way, enjoy the coastal views and visit local attractions. Once in Kii-Tanabe, learn about the Kumano Kodo, the sister pilgrimage of the Camino. This region serves as a gateway to the ancient pilgrimage routes.

Day 4: Journey to Kumano Hongu Taisha and the Nakahechi Route

Ride towards the spiritual heart of the pilgrimage, Kumano Hongu Taisha, passing through traditional villages and scenic landscapes. After visiting the shrine, explore parts of the Nakahechi route, known for its historic paths and lush surroundings.

Day 5: Coastal Ride, Shingu City, and Nachi Falls

Continue your journey along the coastline to Shingu City. Visit the revered Kumano Hayatama Taisha and then proceed to Nachi Falls, a spectacular natural wonder with a sacred shrine nearby. This area beautifully represents the blend of natural beauty and spiritual significance in the Kumano Kodo.

Day 6: Final Stretch to Ise and the Grand Ise Shrine

Conclude your ride through the Kii Peninsula with your arrival in Ise, home to the Grand Ise Shrine, one of the holiest Shinto shrines in Japan. A fitting first 1/2 of the tour that blends physical challenges with spiritual and cultural discovery. There is an optional visit to our favourite Japanese Brewery – Ise Kadoya – as well.

Day 7: Ise to Shirakawago

Transfer into the Alps to explore the World Heritage Thatched Roof Village and enjoy our riverside Ryokan with beautiful outdoor hot springs. This is the transfer day, when the riders will go by train and the bikes and vehicles by road. We all meet in Shirakawago and join the original Noto itinerary

Day 8: Cycle from Shirakawago to Takayama

Today, you’ll embark on a scenic ride from the picturesque village of Shirakawago to Takayama. This route winds through the heart of the Japanese Alps, offering breathtaking views and a chance to immerse yourself in the serene beauty of the mountains. Upon arrival in Takayama, explore its well-preserved old town, known for its beautiful architecture and local artisan shops. In the evening, enjoy the sake tasting in our hotel before trying out the local cuisine, it is known for its Hida beef.

Day 9: Takayama to Gujo

After breakfast, set off from Takayama, cycling through the charming rural landscapes of central Japan. Today’s journey takes you to Gujo, a town famous for its pristine waterways and traditional dances. Spend the afternoon exploring Gujo’s historic streets and unique cultural heritage. Traditional industries like sake brewing and food replicas offer an authentic Japanese experience. Our hotel is positioned directly below one of Japan’s most well-appointed castles, with 300-degree views down all the mountain valleys.

Day 10: Gujo to Gifu

The ride from Gujo to Gifu takes you through the tranquil countryside, along streams and rivers with crystal clear water. Gifu is known for its historic significance and natural beauty, including the stunning Nagara River and the traditional cormorant fishing. Explore Gifu’s rich history, perhaps visiting Gifu Castle or walking along the river in the evening after our celebratory dinner to witness the centuries old cormorant fishing method.

Day 11: After Breakfast, Return to Kansai Airport or Rest Day in Kyoto

On the final day, you can return to Kansai Airport for your journey home or enjoy a rest day in the historic city of Kyoto.

Tour Highlights from the Kii Peninsula

Wakayama’s Historical Charm: Begin your adventure in Wakayama, a city steeped in history and home to majestic castles and serene shrines. Immerse yourself in the vibrant local culture before setting out on your cycling expedition.

Kumano Kodo Pilgrimage Trail: As you pedal through the Kii Peninsula, you’ll trace the footsteps of ancient pilgrims on the renowned Kumano Kodo. Marvel at towering cedar trees, charming villages, and sacred shrines hidden within the mystical forests.

Scenic Coastal Routes: Cycle along the Pacific coast, where the rhythmic sound of crashing waves accompanies you. Enjoy panoramic views of rugged cliffs, sandy beaches, and the expansive blue ocean – a truly mesmerizing backdrop for your journey.

Hot Springs Oasis: Rejuvenate your body and soul in traditional Japanese hot springs, or “onsen,” scattered along your route. Relax in the therapeutic waters, surrounded by nature’s beauty, and indulge in the serene ambience of these hidden gems.

Culinary Delights: Savor the flavours of local cuisine as you traverse charming towns and villages. From fresh seafood to regional specialties, each meal is a culinary adventure that complements your cycling experience.

Ise Grand Shrine: Conclude your journey in Ise, home to the revered Ise Grand Shrine. This spiritual oasis is a testament to Japan’s ancient Shinto traditions.

Once in the Japanese Alps, traverse untouched landscapes and meander through towns and temples that have stood still in time for over four centuries.

The Kii Peninsula

The Kii Peninsula, situated in the Wakayama Prefecture of Japan, is a captivating region renowned for its rich cultural heritage, lush landscapes, and the spiritual Kumano Kodo pilgrimage routes. Cyclists exploring the Kii Peninsula are treated to a diverse terrain that encompasses coastal roads, dense forests, and mountainous trails. The winding paths offer a unique cycling experience, allowing riders to absorb the serene beauty of the peninsula while traversing through ancient pilgrimage routes.

At the heart of Kii Peninsula’s cultural tapestry is the Kumano Kodo, a network of pilgrimage trails leading to the sacred Kumano Sanzan shrines. These trails, deeply embedded in Shinto and Buddhist traditions, beckon both pilgrims and cyclists alike. The Nakahechi route, starting from Tanabe City, is a popular choice, taking riders through picturesque landscapes and quaint villages.

Cycling along the Kumano Kodo provides a profound connection with nature and spirituality. The journey allows cyclists to visit sacred sites, appreciate the tranquillity of moss-covered stone paths, and witness the fusion of religious traditions with the natural surroundings. The Kii Peninsula, with its cycling-friendly routes and spiritual allure, presents a harmonious blend of physical activity, cultural exploration, and contemplation amid the serene beauty of Japan’s historic landscape.

Portrait of Sultan Suleiman I by Italian painter Titian, edited by Büşra Öztürk

Portrait of Sultan Suleiman I by Italian painter Titian, edited by Büşra Öztürk Battle of Mohacs, 1526

Battle of Mohacs, 1526 Map of the Ottoman Empire, 1570, Everett Collection Historical via Alamy

Map of the Ottoman Empire, 1570, Everett Collection Historical via Alamy Portrait of Roxelana, titled Rossa Solymannı Vxor

Portrait of Roxelana, titled Rossa Solymannı Vxor

Kobo Daishi (Kukai), via Tricycle Buddhist Review

Kobo Daishi (Kukai), via Tricycle Buddhist Review Portrait of

Portrait of  Statue of

Statue of  Danjō-garan, head temple of Shingon Buddhism, Mount Koya

Danjō-garan, head temple of Shingon Buddhism, Mount Koya Shikoku Henro (Shikoku Pilgramage)

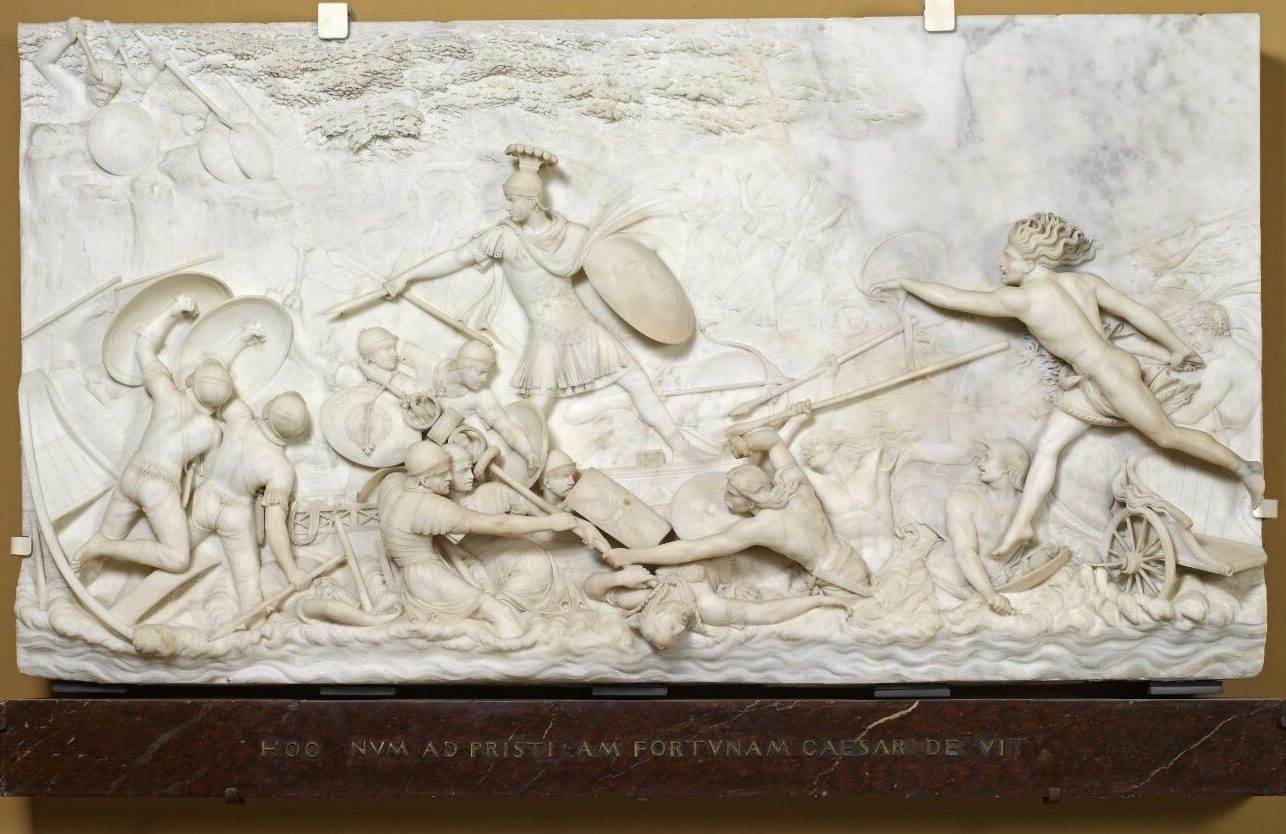

Shikoku Henro (Shikoku Pilgramage) John Deare’s marble relief of Caesar’s invasion of Britain, on display at the V&A, London

John Deare’s marble relief of Caesar’s invasion of Britain, on display at the V&A, London Print by William Sharp, from the engraving by Thomas Stothard, displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Print by William Sharp, from the engraving by Thomas Stothard, displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Hadrian’s Wall

Hadrian’s Wall Roman Baths in Bath, UK

Roman Baths in Bath, UK Photo credit, History Skills

Photo credit, History Skills